What is 'The Trees'?

It’s a podcast.

Each episode features a single question and guests who remind me of my journalist dad’s extraordinary friends.

Media consultant, radio/podcast producer, and sailor Robert Ouimet.

If not for [blank]?

Aboard his 22' Catalina, Matsu.

He gathered them in endless combinations at New York City dim sum brunches —

2,546 Saturdays in a row, between 1966 and 2015.

Photographer, orchestral clarinetist, and author Arlene Alda.

Who helped make you who you are?

In her and her husband Alan's Upper West Side New York City apartment after the recording session.

Eleven-year-old, 1980 me called these folks 'the trees'.

Fifty-six-year-old, 2025 me, ridiculously, still does.

New Yorker magazine cover illustrator, and author Christoph Niemann.

Can you show me some physical artifacts that represent the people who had a personal impact on you?

In his Berlin studio after the recording session.

Slate Political Gabfest Host and CEO of CityCast, David Plotz.

Who helped make you who you are?

Near his home in Washington, DC.

How do I listen to more episodes?

I send out episodes via email. To get on the distribution list, shoot me an email me at ted@thetre.es.

Artists Joel Newton, Jonathan Bernstein, and Paul Carlon.

What is 'elegance'?

Joel, Jonathan, and Paul.

What's this I hear about retreats?

From time to time, I'll gather together a bunch of former episode guests —

for a few days, someplace beautiful.

Katie, a set designer, and Eugene, a comedian and actor; knight in tarnished armor and Peggy, a bookseller; vegetarian pigs; and chef Cali; during a 25-person, 3-day, private-chef-equipped destination retreat at Temple Guiting Manor in the English Cotswolds.

With my dad, Sy, and his brother, Boris, a radiologist. At Glen Wild Lake, New Jersey, 2004.

Little Oscar and his first Newfoundland, Tatou (they were a bit famous on Youtube for entertaining each other).

I have a BA in Music (Cornell University ’90).

Until 2012, I worked at technology companies, including Sony and IBM.

From 2012 to 2020, I helped a small cadre of technology CEOs find specialists to tackle acute business challenges.

One of my clients, CEO Phil Caravaggio, collaborating with Rodrigo Corral on the book design for Ray Dalio's New York Times bestseller, 'Principles.'

Why do you call these folks 'trees'?

The first time dad brought me along to one of his brunches, in 1980, everyone at the restaurant was wearing 'Hi Ted! I'm...' name tags.

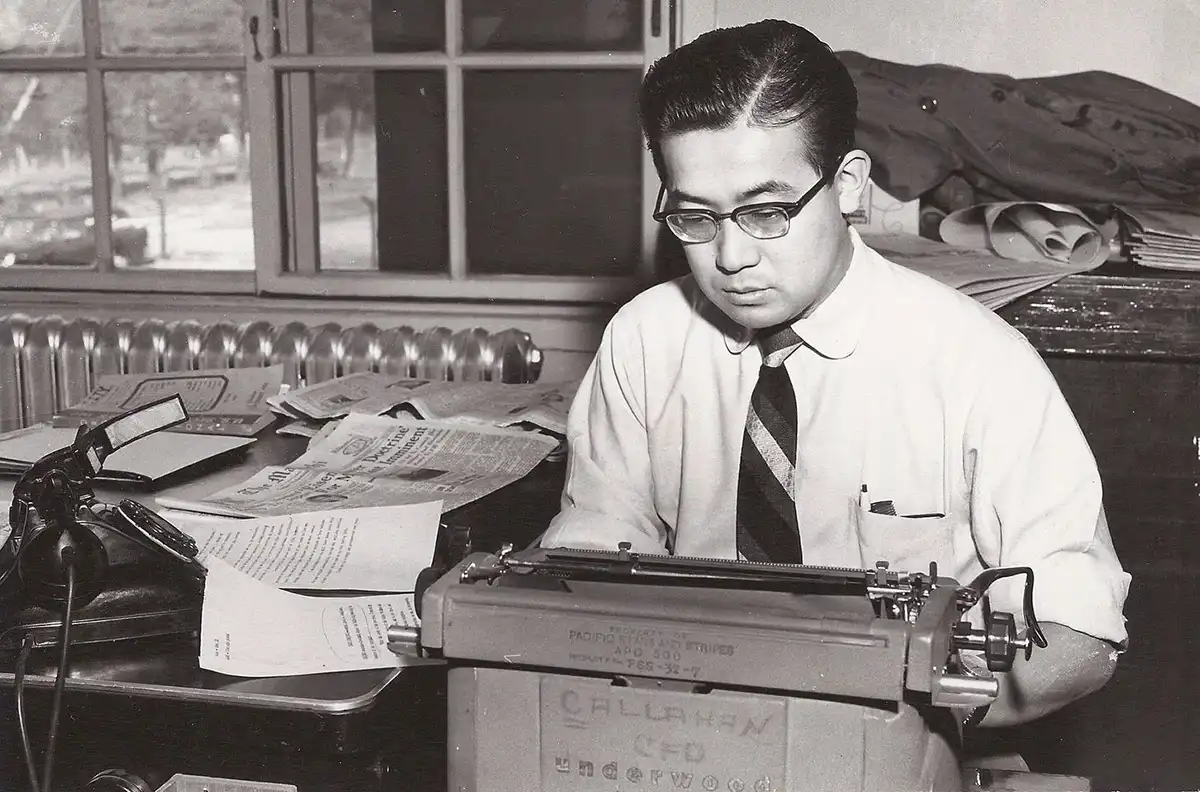

Can you tell me more about your dad?

My dad, Sy (1930-2015), and his dad, Ted, had the same sense of humor.

During the weekend and after school, working together in the family’s Brooklyn candy store, dad and Ted spent much of the time trying to make each other laugh.

In the evening, they’d listen to radio comedy variety shows like Texaco Star Theater.

In New York's Central Park, near his Upper West Side apartment, 2001.

In 1949, a year after high school, dad’s favorite comedian, Sid Caesar, got his first television show, the [Admiral Broadway Review](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AdmiralBroadwayRevue).

By the time the first episode ended, dad had figured out what he wanted to do with his life. He was going to be a television comedy writer.

The next day, while working alongside his mom at the store, dad announced his plan —

“I’m going to be a comedy writer for Sid Caesar’s Admiral Broadway Review.”

She was not amused.

Anna, dad’s mom. Date and circumstances unknown.

Dad, however, was dead serious. He began to ply his craft by writing stand-up bits during the week and heading to the Catskills on the weekends (four hours each way, via subway, bus, and hitchhike) to hawk them to Borscht Belt comedians.

Fort Lee High School, next to the New Jersey side of the George Washington Bridge. Dad hitched rides to the Catskills from the sidewalk out front. Weirdly, in 1986, I ended up graduating from there.

He was well on his way to a career as a television comedy writer. But the Korean War and the draft derailed him. Dad wanted to avoid combat at all costs, so he put his aspirations on hold and enlisted. With a plan.

Growing up in the rough, ethnically divided neighborhoods of post-Depression Brooklyn, and being the man of the house from age 14, he became exceptionally street smart. He could quickly assess people and their motivations, avoid pickpockets, trade favors, and talk himself out of any pickle.

Looking south over the Upper West Side of Manhattan, 1951.

He was also conversant in Russian, which his parents had spoken at home (along with Yiddish) when he was small.

All of this gave dad the idea to apply to the US Army Language School (now called the Defense Language Institute) in Monterey, California. This, he schemed, would enable him to finally become fluent in Russian, meet cute girls on the beach, and groom himself for a commission as an Army intelligence officer, based in Europe, in charge of recruiting and handling Soviet spies, a safe 4000+ miles from armed combat.

Monterey, CA, amazingly, is one of the world's most international cities.

Right after he got to The Times, however, an old friend from his days inside the Borscht Belt got hired to write for [Get Smart](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GetSmart)_, a TV comedy about a bumbling secret agent.

It seemed like some kind of omen to dad, and, for a few weeks, he contemplated sacrificing his career as a journalist to follow his friend out to Hollywood. For various reasons, it didn't happen.

Created by Mel Brooks, arguably Sid Caesar’s most important writer, and Buck Henry.

Funny enough, dad did eventually become a bonafide TV comedy writer (while still somehow remaining a serious journalist) when Reuven Frank, the President of NBC News, recruited him to join [Weekend](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weekend(1974TVprogram))_.

It was the first sardonic, long-form news show on network television, running once a month, in Saturday Night Live’s time slot, when SNL was taking the week off.

I'm convinced it's the (mostly forgotten) great grandfather of The Daily Show and Last Week Tonight.

An article about the show (and dad) from TV Guide.